Japanese Green Tea

Japan may be a small country in terms of area, but its distinctive green teas occupy a prominent position in the world of tea.

There's something substantial, savory, and nourishing about Japanese green teas that I don't get from others. For the past 20 years I've worked outdoors a lot. Initially, when the weather turned cold each year I had difficulty getting warm—that was until I discovered these teas. They could warm me down to my toes and prepare me for another session outside. Despite this, they also rank among my favorite teas chilled! (See Iced Tea.)

Very little of Japan's green tea is exported, although in recent years it has found an enthusiastic audience around the world. Seek some out and let them work their magic on you!

The Character of Japanese Green Teas

Green teas from Japan—like other green teas—are minimally processed, so their dominant characteristics are fresh taste and light color.

Heat, in some form, is applied to all green teas early in their processing to "fix" the leaves. Fixing stops the chemical reactions of oxidation that darken and make teas stronger (See Processing Basics). Various methods can be used to fix leaves, but Japanese tea-makers almost exclusively employ steam. This results in bright green teas with a distinctive vegetal taste that can have hints of lemon or kelp. Typically they are stronger than Chinese green teas.

Sometimes the twigs or stalks from tea plants, or even rice are added to Japanese green teas. These additions result in teas that possess toasted and woody flavors. While they're still light, they have a hearty, yet mellow, character.

A Very Brief History of Japanese Green Tea

Although research shows that tea first arrived in Japan from China in the 6th century, the Japanese only began to place their unique stamp on it about 500 years ago. Since then, though, its production has been marked by a lengthy list of innovations.

Adding toasted rice to tea to make Genmaicha was done in the 16th century or earlier, probably as a way to make the tea last longer. The 16th century also marks the time when the tea ceremony (Cha No Yu or Chanoyu) was developed. This ritual established the link between tea and Buddhism, a relationship that continues today.

The mechanization for which Japanese green tea is known began in the 18th century with both harvesting and processing techniques.

In the 20th century a high-yielding tea plant clone named 'Yabukita' was developed. It is well-suited to Japan's climate, mechanical harvesting methods, and tastes. It continues to dominate the tea gardens of Japan.

After WWII the Fukamushi method of deeply steaming tea leaves was invented. The process breaks the tea leaves apart more than does traditional steaming, an attribute that speeds up the tea's production. Ultimately, it also shortens the time required to brew a cup.

Where Japanese Green Tea is Produced

Japan's tea production is all about efficiency, and doing a lot with limited space. The nation spans a latitude range from about 30–45° North of the equator, but a rugged mountain chain runs through the central spine of the islands that takes up over 75 percent of the nation's area. Most tea gardens are situated on rolling hills at low elevations outside the city centers, industrial areas, and intensively farmed food crops. As a result of limited and expensive land, tea gardens are tremendously efficient in their layouts and cultivation methods. Closely spaced rows of tea plants maximize space and facilitate faster harvests because of their regularity and close proximity.

While tea is grown as far north as Hokkaido island and as far south as the Ryukyu islands, the bulk of tea production is confined to Kyushu and Honshu islands.

The Uji area near Kyoto is the oldest of the tea-producing regions, and it makes the finest and most expensive of Japan's teas. The bulk of the nation's green tea production takes place in Shizuoko prefecture on Honshu island.

Major Styles of Japanese Green Teas

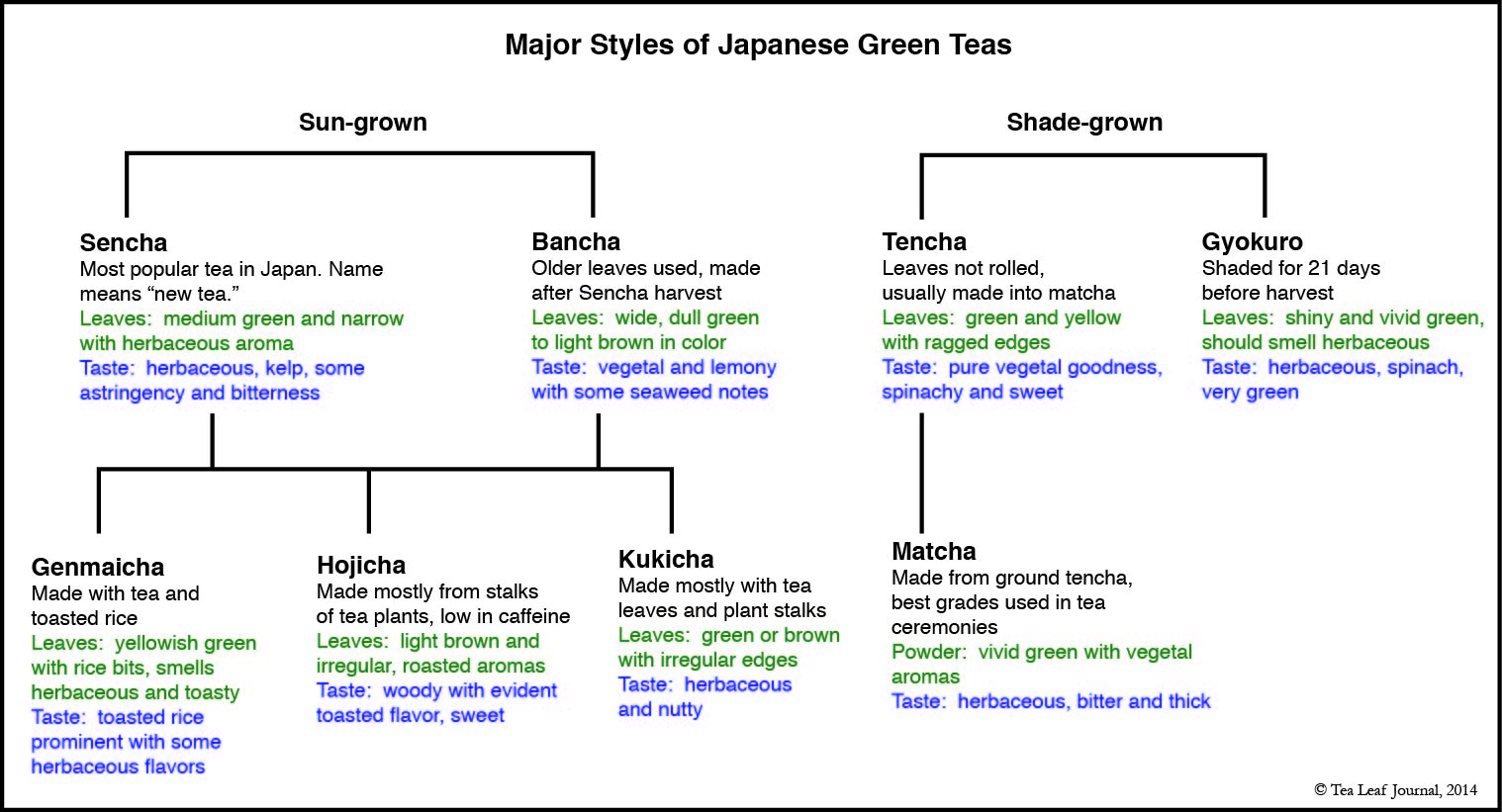

The different styles of Japanese green teas are each quite unique, but a major distinguishing factor is the sun exposure they received when growing.

Tea usually grows in sunny conditions. Sencha and bancha are Japan's sun-grown teas and are the most popular for everyday drinking. The youngest leaves of the tea plant are used to make sencha while leaves for bancha are harvested from slightly older leaves. Both are light-colored, vegetal teas when brewed. Sencha is considered to be the more flavorful of the two; bancha is a bit stronger.

Sun-grown plants and teas form the basis for genmaicha, hojicha, and kukicha. Each of these is a little unusual in its makeup, but their toastiness gives them a distinctive added dimension.

The Japanese also use a shade-growing technique for their finest teas. Up to three weeks before harvest, tea plants are covered so that only dappled sunlight reaches their leaves. As a result, minimal photosynthesis takes place in the plant, leaving chlorophyll, theanine, and amino acid levels higher than they would be in sun-grown plants. Shade-grown tea tends to be darker and greener than its sun-grown counterparts, and it has less astringency.

Tencha and gyokuro are the two primary shade-grown teas. Of Japan's green teas, these are the most likely to be processed by hand. Most tencha is ground into matcha powder used in tea ceremonies.

The following table illustrates the most common types of Japanese teas with a few notes about each, the dry leaves' appearance and each tea's taste.

What else makes Japanese Green Teas Different?

Except for the most exclusive teas that are made by hand, tea-making is an automated process in Japan. Plants are harvested with tools ranging from hand shears to plucking machines before being mechanically processed.

Most teas in the world are processed close to where they are grown, but this marks another point of departure for Japanese green teas. They undergo two different stages of processing that usually take place in separate locations. During the first stage of manufacture tea leaves are harvested, steamed, and rolled while partially drying. Stored properly, these steamed leaves are stable and fit for travel.

In the second phase, the tea is transported to another facility where it is roasted and dried further—processes that bring out the subtle flavors and aromas of the specific variety.

The main thing to know about this two-part method is that the finishing of the tea is highly individual to the tea-maker. So a hojicha from one producer will taste different from a hojicha from someone else. If you've fallen for a particular Japanese green tea, try to buy from the same producer to get a consistent product.

What to Look for When Purchasing

The table above details characteristics to look for when purchasing Japanese green loose tea. As always, it's most important to choose a tea that appeals to you.

Keep in mind that Japanese teas are composed of broken and fragmented tea leaves. This is the result of their processing and not an indication of lesser quality.

Depending upon where you live, a wide range of Japanese greens may not be available locally. My introduction to this unique group of teas was through Choice® teas. They carry a nice selection of these teas (many in teabag form in you're not ready to commit to whole leaf), are reasonably priced, and are widely distributed.

How to Brew Japanese Green Tea

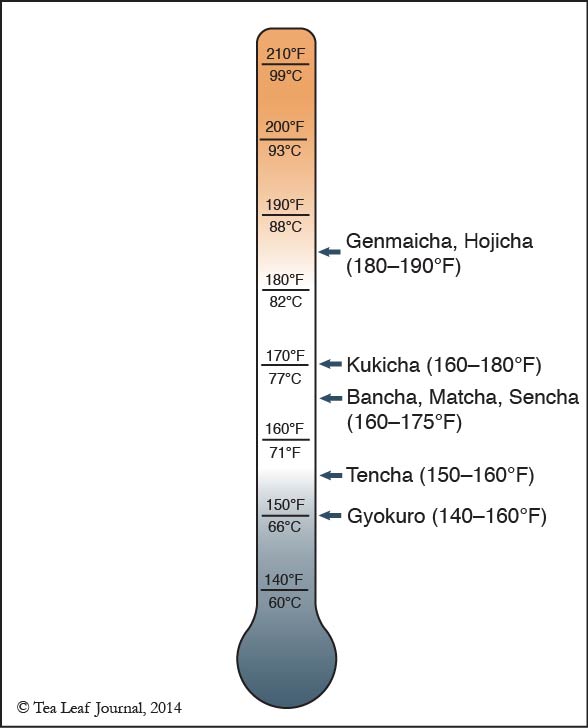

Green tea requires cooler water for brewing than most other teas; infusing with the recommended temperature water will keep its flavors and healthful compounds intact. Ideal water temperatures range from 140°F (60°C) for a fine gyokuro to 190° (88°C) for a genmaicha or hojicha. See the chart below for general guidelines, but consult your tea's packaging for specifics.

Because of its small leaf size, exercise care when infusing Japanese green teas. Initial infusions can be as short as 30 seconds, with subsequent infusions gradually increasing to 2–3 minutes.

Storage Tips

Japanese green tea often will be sold in refrigerated, vacuum-sealed packages. Too many trips in and out of the refrigerator will degrade the tea's quality, so keep a small amount out at room temperature for daily brewing.

If your tea isn't refrigerated, treat it as you would other teas. Keep it in an airtight container at room temperature and out of direct sunlight. Japanese green teas are delicate, so try to use them within eight months.